Russia’s artistic legacy is of Imperial Tsarism, industrial Communism and of some of the finest and most unique art, theatre, literature and architecture in Europe. When the Revolution began in 1905, it marked not only a political change but also a change in Russian culture. It acted as a catalyst for reordering and modernising a country which had severely lagged behind the rest of Europe for most of its existence. The artistic movements which were already in existence in the Imperial era emphasised elitism and elegance. Following the revolution though these had adapted and modernised or perished. While the rest of Europe was experiencing a Fin de Siècle or Belle Époque, Russia too was undergoing a similar transformation referred to as their ‘Silver Age’ which embodied the history of art, philosophy, aesthetics, and literary criticism[1]. This era was at its height when revolutionary philosophies seeped into artistic movements, and when the Revolution transpired it became obvious that more than politics had changed. Indeed, there were few new artistic movements after 1918 that could not trace their roots back to Silver Age ideas.

The later Imperial years, from 1860 onwards, marked a dramatic change in artistic thought and expression. Russia was experiencing a steady stream of social development, an increased emphasis on education was seen, and whilst being run mostly by the church, witnessed literacy rates rise from 6% in the 1860s to an estimated 28% by 1913[2]. This was also an era where Russia produced eminent contributions in science and maths, such as Lobachevsky, Pavlov and Mendelev. Social sciences too became more prominent, History in particular became a well studied field as Russian academics explored their national historiography. Fine art during the first decade and a half of the 20th Century was divided between artists seeking to continue celebrating traditional styles, and those seeking to express the progressive bold new styles. John Bowlt suggests that artists became desperately aware of the “fundamental displacement of social, ethical and cultural values”, exacerbated by the 1905 uprisings, and they fled from a “mundane reality” into an etherial and unorthodox world[3]. Bowlt goes on to suggest that another reason for returning to traditional natural art was the fear and intrigue caused by Russia’s rapid industrialisation. However the decadence of the Imperial era was drawing to a close and for a brief final period Russian art lacked a purpose or reason[4].

Symbolism was a short lived movement, but developed highly emotional and spiritual pieces of work expressed mostly through poetry. Early symbolists, such as Vladimir Solovev expressed close connections to nature, and his successors, such as Aleksandr Blok would build on the principles of nature and country to write poems about Russia and nationalism. Blok would span pre-Soviet and post-Soviet genres, and the maturing from futility to utilitarianism in art movements. Peter France highlights how Blok’s works conclude with a sense of hope, unexpected joy and resurrection[5], not only being inspired by his country but also being influenced by the revolutionary ideology. Symbolism though reached its climax around 1905 and spawned a progeny in the form of the Acmeists. Whilst the Symbolists had sought to imply and infer through metaphors and allegories, the Acmeists favoured unambiguous imagery and emotions in their writing. Poets such as Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam flourished in the movement, and Blok too adapted to the new style. Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal argues that the downfall of symbolism was its cryptic nature, and highlights that whilst they were trying to influence the Russian people, even artists had difficulty understanding one another’s work[6]. Symbolism emphasised the elitist nature of a lot of art from the start of the 20th Century, with a lack of accessibility for the proletariat, with many of the poems written seemingly accepting a revolution as the next symbol.

Another of these ‘decadent’ movements appeared in architecture in the form of ‘style moderne’, a cousin of Art Nouveau. The principles of Art Nouveau are organic, natural and creative design and applied mostly to architecture and graphic design. William Brumfield’s article on anti-modernism points out that the movement came about following a shift to urbanisation, but was primarily intended for Russia’s bourgeoise[7]. As an artistic movement it was criticised as being ‘aristocratic aestheticism’ but also because critics, in particular the Mir Iskusstva, saw it as a threat to Russia’s traditional buildings and design. This led to the counter movement of neo-classicism which favoured classic designs and icons over the modernity of style moderne. Paradoxically the Neoclassical movement was responsible for more urban development than style moderne ever did, and was responsible for buildings such as the Moscow State Pedagogical University (built 1910-1914) and many large apartment buildings in the capital.

The Realism and Classicism that had been the trademark movements of the 19th Century were at worst in their death throws and new movements like the Mir Iskusstva (The World of Art Movement) actually rejected realism. They acted as a prominent force for artistic change in the pre-Revolutionary era, through a collection of revisionist artists and a magazine which publicised their philosophy. A. Benois initiated the movement as a means to counter the modern and pro-Positivist themes in art which they saw as lower artistic standards, their philosophy being ‘Art for Art’s Sake’[8]. Despite a large following the magazine became unpopular for its approach to art criticism, with articles attacking specific artists and accusations of foreign influences damaging Russian styles[9]. The movement saw art as a force for educating the masses, with morally or socially uplifting subjects, and supported by national identities. They welcomed traditional subjects, in traditional media: illustration, painting and writing. It particularly promoted folk art and handicrafts, hoping that the Russian population would value them over the ‘mass-produced commercialised’ art[10].

However, no amount of historical nationalism and retrospective art could prevent revolutionary philosophy from infiltrating movements following the 1905 uprisings in Russia. Whilst the political revolution had failed the educational revolution was underway, with the years following the uprisings being the years that Russian modernism would flourish. The national art history that Benois had craved was slowly developing, in contradiction to his ideals of outright traditionalism. Modernism and futurism were the new favoured styles, as they too had changed to address more social themes.

Neo-primitivism was an evolving style. It bridged the divide between the Mir Iskusstva school of thought and the futurist style, embracing traditional folklore subjects and expressing them through modern painting. Natalya Goncharova’s (1914) image of a woman in peasant costume expressed no attributes of Realism and lacked in finesse, similarly Malivech’s 1912 painting ‘Morning in the Village after a Snowstorm’ demonstrated a highly stylised cubist interpretation of a traditional scene.

‘Morning in the Village after a Snowstorm’ – Kasimir Malevich (1912),

In comparison the ultramodern Futurist movement whilst defined as ‘Russian Futurism’ was ultimately a facsimile of the Italian Futurism outlined by Filippo Marinetti’s ‘Futurist Manifesto’ from 1909. The principles were outlined as: “anarchical vitalism, defiant rebellion against ‘passiesmé’ in the arts as well as in society, and confidence in the achievements of technological civilisation”[11]. Marinetti’s vision manifested itself primarily in Russian literature and poetry. Writers such as Velimir Khlebnikov and Vladimir Mayakovsky embodied the spirit of futurism in the writings. Marinetti’s concept embraced technology, and the Russian writers developed their own ‘transrational language’ or ‘zaum’ which used onomatopoeic words to convey sounds and mechanisation[12]. Khlebnikov’s poem ‘The Grasshopper’ uses “zingzinger” and “ping” to express noises. In comparison to the romanticism of Pushkin and the realism of Dostoevsky, the futurist poets showed a progression and modernity, and a want for change.

‘Red Rayonism’ – Mikhail Larionov (1913)

Rayonnism was a visual development of futurist ideas by Mikhail Larionov in 1911. Whilst abstract paintings are the ideas and reactions to a subject Rayonnist artists used bold colours and brush strokes to evoke not the object but the “rays emanating from the object”[13]. Similar in style and subject to Italian Futurist paintings artists depicted modernity, speed and technology. Larionov saw Rayonnism as more than an artistic style or a fashion, but “literal renderings of physical and philosophical fact”[14]. In comparison to Realist style or ‘style moderne’ which promoted literalism and inanimateness, Larionov’s movement embodied modern themes of the era: speed, light and space. Suprematism was a similar movement started 1915-1916, and pioneered by Kasimir Malevich which built on Larionov’s principles of linear simple compositions, but reduced this subject and focused on basic shapes and forms[15]. ‘Yellow Quadrilateral on White’ (Malevich, 1916-1917) and ‘Black Square’ (Malevich, 1913) are key examples of the simple style of painting and even the titles of the paintings imply a minimalist and functional approach to the art form. Charlotte Douglas argues that Suprematism directly turned its back on the Symbolist philosophy of reason and purpose[16], instead its simplicity actually represented nothing and was the creation of a new reality, and in many ways represented Russia: as a new and fresh system. Suprematist paintings were the direct opposite, both aesthetically and philosophically to the detailed and literal works of Realist artists such as Repin.

Bowlt hypothesises that the Silver Age was an incredibly confused era in art history, which he argues derived partly from the fact that the Russian Silver Age was an extremely varied, contradictory and elaborate phenomenon”[17]. The era demonstrated a transition in Russian art. From the classical Realist paintings of Repin; to the traditionalist revival of the neo-primitivists; to the antagonistic Futurists. The years between 1905 and 1908 marked a turning point for the art movements of Russia as the implications of the 1905 uprisings began to sink into artistic philosophy. As the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, there was drastic political and social upheaval. This was not just a move for the future though, as new traditions were quickly established, religious holidays were replaced with new holidays[18] and Russia’s history began to seem archaic and bourgeois. And the revolution did not stop in October 1917, as the Civil War continued from October until 1923. However, the revolution was not necessarily a catalyst for change within the art movements. Many of the seeds of revolution and modernity had been sewn a decade earlier. Early Soviet artists had already decidedly rejected the old styles, and were then seeking to use the new space to further their new movements.

The revolution had political and social ramifications, the proletariat worker became highly valued. Their significance was shown in the Proletkult movement which encouraged art ‘about the people, by the people, for the people’. The Proletkult was funded and controlled by the Bolshevik régime, with the intention of creating artless classless art which was universally accessible[19]. Initially, there was a Pluralist society which welcomed creative development. A problem which arose out of this was anti-intellectualism and anti-elitism. Whilst before the revolution art had been mostly free of political influence, now it was critical to developing art. In many ways Anti-intellectualism became an artistic style in itself, by promoting its own philosophy of anti-authority and anti-heirarchy in art. One poet wrote: “Destroy the churches, those nests of gentry lies; Destroy the university, that nest of bourgeois lies; Drive away the priests, drive away the scientists! Destroy the false gentry and bourgeois heavens”[20]. This led to a heightened sense of class consciousness, and an aggressive anti-elitist crackdown as Soviet era progressed artists came under pressure to conform to new – arguably more Soviet – styles. Peter France examples Anna Akhmatova and explains that she continued to write about the same insecurities as in her earlier work, however the Central Committee of the Communist Party found her work ‘anachronistic’ and had her work censored[21]. Formalism too was a style which came under attack in the Soviet era. It was a movement which grew out of the principles of Futurism, embracing the modernist subjects and styles but demanded a more coherent and erudite format. To those who valued class equality, Formalism was a style which embodied an outdated technique and demanded an educated audience.

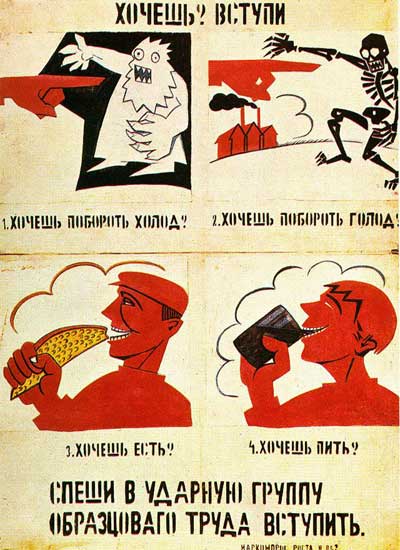

Agitprop was one of the few new movements in the post-revolutionary era. It used pamphlets, plays, cinema, and the fine arts to simply and ideologically address the working proletariat. This was partially as a result of being influenced by the Futurists, but also because literacy was still incredibly low. The Bolsheviks still needed to maintain influence over their population and the best way to express this influence was at a basic graphic level.

Vladimir Mayakovsky Agitprop poster, “Want it? Join” (Date unknown)

Another emerging style was Constructivism which took its basis from earlier Futurism. It was a movement which used the same geometric shapes, lines and bold colours as the Futurists but their philosophy conformed more to the Soviet demand for a utilitarian approach to everything, this included art. However this created divisions between artists, particularly in the Constructivists who debated utilitarian purpose in their work and whether it was an ‘organising principle’ or an ‘aesthetic function’[22] and combining and balancing them to create a composition. Constructivism started and developed the first true Russian ‘machine age art’, rejected easel paining, but most significantly embraced functionalism and utility and so quickly expanded into more utilitarian purposes. Contemporary critics had seen the art produced by the movement as literal design prototypes and the main proponents soon found themselves designing fabrics, clothing, furnishings in the tone of Russian industrialism[23]. It was a highly influential style which penetrated all aspects of Soviet society in a way that previous movements had been purely aesthetic and artistic, as Bowlt highlights there was no “Cubist architecture, no Symbolist chairs, and no Realist dresses”[24].

Fashion was one of these branches, and the Constructivists found their style created clothing which was “simple, cheap, hygienic, easy to wear, and industrial”[25]. Liubov Popova was one of the key designer of the era. Her lack of institutionalised artistic training was quintessential of the era, being made by the proletariat and free of any ‘elitist’ influence. Povova’s designs shared the Suprematist’s use of simple geometric shapes, however her canvas was the body and relied on the compositions ability to hang off the body. Whilst previous artistic movements had been either in the 3D form of sculpture, or 2D form of painting, the Soviet interest in fashion applied the 2D principles to a 3D surface.

Architecture was another of the 3D developments which saw aesthetic changes by Constructivism. As with the rest of their work functionality became paramount, with the aim being to unite living, working, and recreational spaces[26]. The beacon, quite literally of the Constructivist architectural movement was the Shukhov Radio Mast in Moscow. The essence of Constructivism was modernity, and their ability to apply their philosophy to all every day media meant that the Constructivism artists effectively designed the revolution.

The Shukhov Radio Mast in Moscow

At the same time the fine arts had in no way been forgotten or replaced. The descendants of Futurism, in the same way as the Constructivists, had utilised the new open space for artistic development and media. However the Constructivists’s utilitarianism was a minor part of the new Futurist movement. Suprematism continued into the early Soviet years continuing to create 2D artwork of a wholly aesthetic nature. Other branches of Futurism spread into literature and music expressing the industrial and mechanical themes which had previously only been expressed in paint. Arseny Avraamov’s ‘Symphony of Factory Sirens’ used ship sirens, vehicle horns, fog horns, factory sirens and artillery to create a cacophony of industrial tones. There was also the development of ‘conductorless’ orchestras, created partially due to a lack of skilled conductors in post-revolutionary Russia but also the belief that conductors “prevented good musicians from expressing their artistic individuality”[27].

Futurism was not just about the artistic style but also about the new media. Cinema became a new form of artistic expression. Though as new media was developed their was an realisation by the régime that the media should be utilised to promote their Bolshevik ideals. Sergei Eisenstein’s films ‘October’ and ‘Battleship Potemkin’ acted as propaganda for the state, as highly idealised interpretations of history.

Another pre-revolution movement that saw a comeback was Realism. Now a movement that had been highly influenced by the Proletkult and modernist styles, Socialist Realism was a state promoted artistic style. In place of the elitist archaic style was now a modernised propaganda tool, aimed at “realistically” portraying proletariat life. The Worker Correspondence movement combined journalism with creative writing established a ‘proletarian literature’[28]. In the visual arts too, the proletariat was central. Painters depicted three things: portraits of political or military leaders; historical paintings; and ‘genre’ paintings depicting production lines, collective farming, and domesticity[29]. The post-revolutionary years were political designed to create a new Russia, and whilst the artistic movements were nothing revolutionary, they helped shape the new era both philosophically and aesthetically.

When comparing the movements of both pre and post revolutionary Russia there is a clear progression from Classicism to Modernism, but only at the polar ends of each era. Late Imperial art enjoyed traditional subjects and styles, portraying decadence and archaism. As revolutionary philosophies seeped into the Russian consciousness, there was both an advancement in art but also several movements established to protect the themes of Imperial art. The Mir Iskusstva movement backlashed against the modernism of art, whilst the Neo-primitivists attempted to combine the traditional and the Positivist in their art. However, the Futurist movement best represented their contemporary Russia. The Silver Age then witnessed he most significant change in artistic styles and when the revolution of 1917 came around, much of the revolutionising had already happened.

The art of the early Soviets differed greatly from the art before 1905. The biggest change in society was the militant Collectivism, exhibited by the Proletkult. Great emphasis was placed on industrialism and the proletariat. There was a disappearance of the individual from art in favour of the masses. There was also the development of agitation in artwork, as movements were encouraged to evoke revolution and change. However as Soviet Russia grew, there was a greater stress to conform, and the radical art of 1917 to the late 1930s was lost to Stalin’s cultural control.

Ginny Dawe-Woodings BA MA

- Nicholas V. Riasanosky, Mark D. Steinberg, A History of Russia Since 1855 Volume 2 (2011), p. 444

- Ibid, p. 442

- John E. Bowlt, ‘Neo-Primitivism and Russian Painting’ in The Burlington Magazine (1975), Vol. 116, No. 853, p. 134

- Ibid, p. 94

- Peter France, Poets of Modern Russia (1982), p. 54

- Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, ‘Nietzsche in Russia: The Case of Merezhkovsky’ in Slavic Review (1974), Vol. 33, No. 3, p. 437

- William C. Brumfield, ‘Anti-Modernism and the Neoclassical Revival in Russian Architecture’ in Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (1989), Vol. 48, No. 4, p. 371

- Tamara Talbot Rice, A Concise History of Russian Art (1963), p. 248

- Stuart R. Grover, ‘The World of Art Movement in Russia’ in Russian Review (1973), Vol. 32, No. 1, p. 33

- Ibid, p. 36-37

- Anna Lawton, ‘Russian and Italian Futurist Manifestoes’ in The Slavic and East European Journal (1976), Vol. 20, No. 4, p. 407

- Ibid, p. 409

- Tamara Talbot Rice, A Concise History of Russian Art (1963), p. 262

- Charlotte Douglas, ‘The New Russian Art and Italian Futurism’ in Art Journal (1975), Vol. 34, No. 3, p. 233

- Tamara Talbot Rice, A Concise History of Russian Art (1963), p. 262

- Charlotte Douglas, ‘Suprematism: The Sensible Dimension’ in Russian Review (1975), Vol. 34, No. 3, p. 280

- John E. Bowlt, ‘Through the Glass Darkly: Images of Decadence in Early Twentieth Century Russian Art’ in Journal of Contemporary History (1982), Vol. 17, No. 1, p. 94

- František Deák, ‘ The AgitProp and Circus Plays of Vladimir Mayakovsky’ in The Drama Review: TDR (1973), Vol. 17, No. 1, p. 47

- Leo Pasvolsky, ‘Proletkult: It’s Pretensions and Fallacies’ in The North American Review (1921), Vol. 213, No. 785, p. 539

- Abbott Gleason, Peter Kenez, Richard Stites, Bolshevik Culture (1985), p. 15

- Peter France, Poets of Modern Russia (1982), p. 63

- Briony Fer, ‘Metaphor and Modernity: Russian Constructivism’ in Oxford Art Journal (1989), Vol. 12, No. 1, p. 19

- Catriona Kelly, David Shepherd, Russian Culture (1998), p. 143

- Abbott Gleason, Peter Kenez, Richard Stites, Bolshevik Culture (1985), p. 205

- Ibid, p. 203

- Catriona Kelly, David Shepherd, Russian Culture (1998), p. 144

- Leonid Sabaneev, ‘A Conductorless Orchestra’ in The Musical Times (1928), Vol. 69, No. 1022, p. 308

- Jeremy Hicks, ‘Worker Correspondents: Between Journalism and Literature’ in The Russia Review (2007), Vol. 66, No. 4, p. 585

- Catriona Kelly, David Shepherd, Russian Culture (1998), p. 146