“[Writing] will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

– Socrates (Recalling what King of Egypt Thamus says to Theuth

following Theuth’s demonstration of the invention of writing) [1]

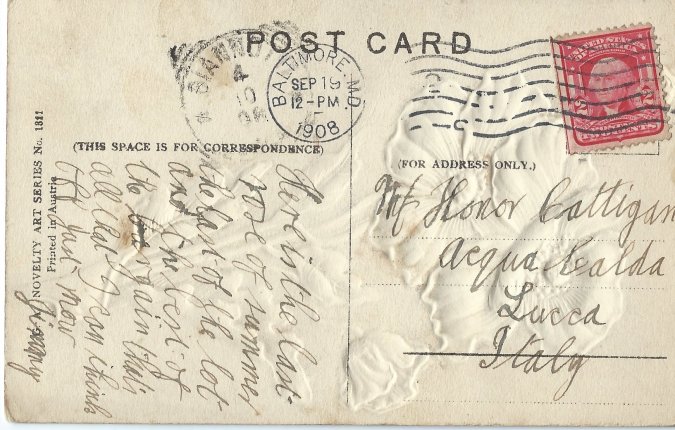

The Titananess Mnemosyne; the Greek personification of memory. (Mnemosyne, Dante Gabriel Rosetti, 1881)

In the Western tradition writing is the exalted form of communicating human thought. Yet it was this same form of communication that King Thamus in Plato’s Phaedrus was convinced would make us forgetful and only offer a semblance of truth.

Archives underpin many of society’s functions – accountability, efficiency, evidence, and the creation of cultural and national narratives and identities. This paper will consider that latter function – if archives are now the constructors of memory, have archives like writing, in Socrates’ words, made us forgetful and, in this sense, have archives undermined society’s memory?

Archives have a complicated relationship with memory. Archival institutions – houses of writing – have claimed to “be”, “contain”, “inspire”, and “support” memory: conversely memory has been said to be “found in”, “contained by”, and “created by” archives.[2] Steven Roger Fischer argued that writing and recording is rooted in human beings’ fundamental need to store information for communication, be it immediately or in the future.[3] Laura Miller suggests a likening between the processes of creating, storing and retrieving memories and the way archives capture, preserve and make available records and archives.[4] Many of the world’s cultures built systems around this principle and where archives find their place in society – as repository stores for this ‘information’. Records, for the most part, represent a tangible form of communication. In contrast oral traditions and the recalling of memories are intangible and fluid in their transmission making them essentially un-archivable.

One of the major ongoing debates in archival science is whether the primary role of the archive is to support evidence or to support memory. Terry Cook examined the various archival paradigms and how they have developed over time to reflect societal trends and expectations. Originally the focus was on the evidentiary nature of archival collections and their use in supporting accountability, but this has now shifted to an identity and community oriented focus.[5] Community and identity paradigms put less emphasis on the authenticity and reliability of records and more what they mean to people personally.

It is important to assess why archivists claim such a bond with memory. Etymologically there is a strong connection between records and memory – the word ‘record’ derives from the Latin recordari combining re and cord to mean to recall ‘by heart’. To record was originally the process of committing to memory, and memory was the capacity for remembering.[6] For a long time archives have monopolised the term ‘memory’, claiming to support, be and create it. There is a prioritisation of an archival interpretation of memory over individual memory and recollection. This comes down to the common conception that tangible primary source material is more valuable as evidence than intangible recollections. In 2012 it came to light that the government had hidden 1.2million sensitive documents in a secret archive in Hanslope Park, in what was deemed to be a sacrilegious attack on data protection laws. Some of the documents related to atrocities during the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya during the. However it wasn’t only the blatant illegality of the secrecy that was disturbing – the fact that the government bodies sought to hide these documents demonstrated an assumption that the victims would have no ‘evidence’ or ‘proof’ based on their memory alone; that individual testimony would not be trusted by itself. Josias argues that the implications for giving or denying legitimacy to past events is when the tension between written and oral sources is often most visible.[7] Trying to combine memory and evidence has historically been a problem for example oral traditions, seen in Aboriginal societies, were only accepted as legal evidence in Canada as recently as 1998.[8] In this sense archives support memory, but only their own archival formulated memory. As Terry Cook argued, “[w]ithout reliable evidence set in rich context, memory becomes bogus, false, wishful thinking, or is transformed into imagination, fiction, ideology.”[9] Archives argue they support memory but really they seek to validate memory, finding comfort in ensuring that memories are true.

Archives’ claims that they ‘are’ or ‘can be’ memory are complex. Memory is an inherently personal practise, unique to what created it, so how can archives claim to control the intangible? Memory is not an unchanging vessel for carrying the past into the present; memory is a process, not a thing, and it works differently at different points in time.[10] Instead of archives claiming to ‘be’ memory, perhaps a better term would be ‘to perpetuate memory’. Isabel Allende claimed that “[d]eath does not exist; people only die when we forget them” and this is perhaps another case where archives support and perpetuate memory.

An individual’s memories can only exist whilst they are alive – in oral traditions what failed to survive in an individual’s memory or be passed on died forever. People’s memories, their own internal records, must have been their most treasured, but most fragile, possessions.[11] Archives are able to ensure that memory, or at least traces of memory, can exist beyond the life of the memory creator. As Jeffrey Wallen puts it, “[o]ur identities are also woven for us, and the archive is the loom.”[12]

A seal discovered in the 1850s led to the discovery of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation. It is suggested that deforestation and a series of invasions contributed to the decline and eventual obliteration of the civilisation.[13] As a consequence of this there is no ‘memory’ of the civilisation, only physical artefacts that need interpretation. This poses the question of what happens when there is evidence but no memory? People can choose to forget – individually or collectively. Whilst it is now recognised that records are products of society and the multitude of structures, biases, systems and agendas that accompany said society, and there is acknowledgement that what has been recorded has been recorded for the purpose of posterity,[14] it is still the intention of archivists to impartially keep records of all history. This can be seen in the Canadian ‘Total Archives’ project – the concept of collecting, or at least attempting to collect, “all aspects of historical development, seeking the records not just of officialdom or of a governing elite but of all segments of a community.”[15] Wallen argues that archival material is imprinted by bureaucracy, that which has been institutionally preserved – “traces of the dead, evidence of the past that has been recorded but not (yet) brought into the public space of the published book, of the library or museum.”[16] Much as the Indus Valley seal connects the present with a lost civilisation, archives connect the present with lost or forgotten individuals and memories. Immortality can be found in the archive.

Within Terry Cook’s community paradigm of archival focus it is clear that archive users want to find their place in their community – to construct a personal identity that also connects them to their surrounding society. Here there is a debate about who’s heritage, or who’s memory is held in archives – the individual or the collective, the elite or the marginalised. The community paradigm also begs questions about formats in archives – oral vs written traditions. For the most part archives privilege what Cook and Schwartz call “mainstream, white, European – North American, logocentric, text-based” archival records[17] over oral testimony, community archive projects, and other non-traditionally created records. As these fall outside the traditional archival boundaries they are often branded as makers not of evidence, but of memory. There is an active movement in archival science to supplement current holdings with oral history projects and other collecting projects that are aimed creating a more ‘complete’ history and memory of various communities.

Many archival processes and theories are underpinned by the life-cycle model which describes a linear projection for the life of a record. From creation to either retention or destruction the role of the record can only exist in one frame of the life-cycle at a time. The records continuum proposed by Australian archivists expands the meaning and use of a record, allowing the record to be both dormant and active at the same time. This pluralisation of properties means a record can exist to support bureaucratic functions and be ‘a memory’ simultaneously. Sue McKemmish argues that there is a perception that records managers are concerned with corporate memory while archivists are concerned with collective memory.[18] McKemmish suggests that the continuum balances these roles.

Mark Greene argued that history is based around reinterpreting the facts of memory, because history, and by extension archives, are inherently untrusting of the merits of memory.[19] The fluidity and continuity of memory does not sit right with archives, who instead demand fixed storage-box models of history.[20] Clearly archives have a relationship with memory but it is troubled and so a particular archival interpretation of memory has developed. This interpretation is much more closely aligned with much of the literature on mnemonic devices – after all, as discussed earlier, it is physically impossible to archive something as abstract as a memory. This paper will now examine archives as mnemonic devices and as repositories of mnemonic devices.

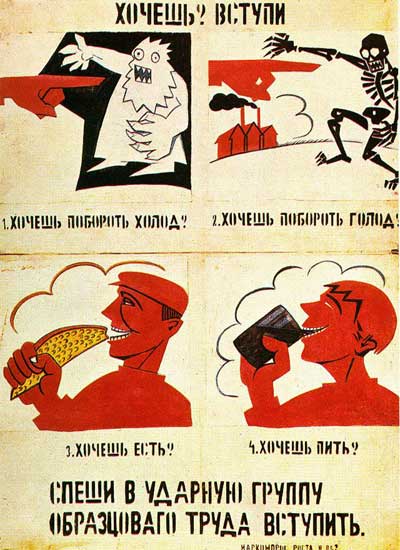

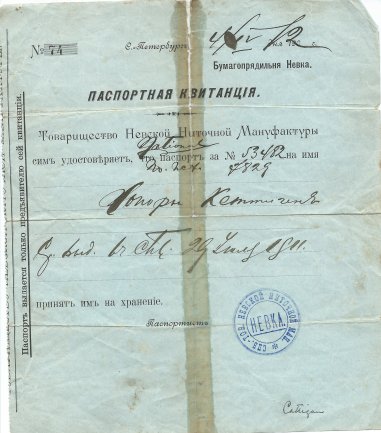

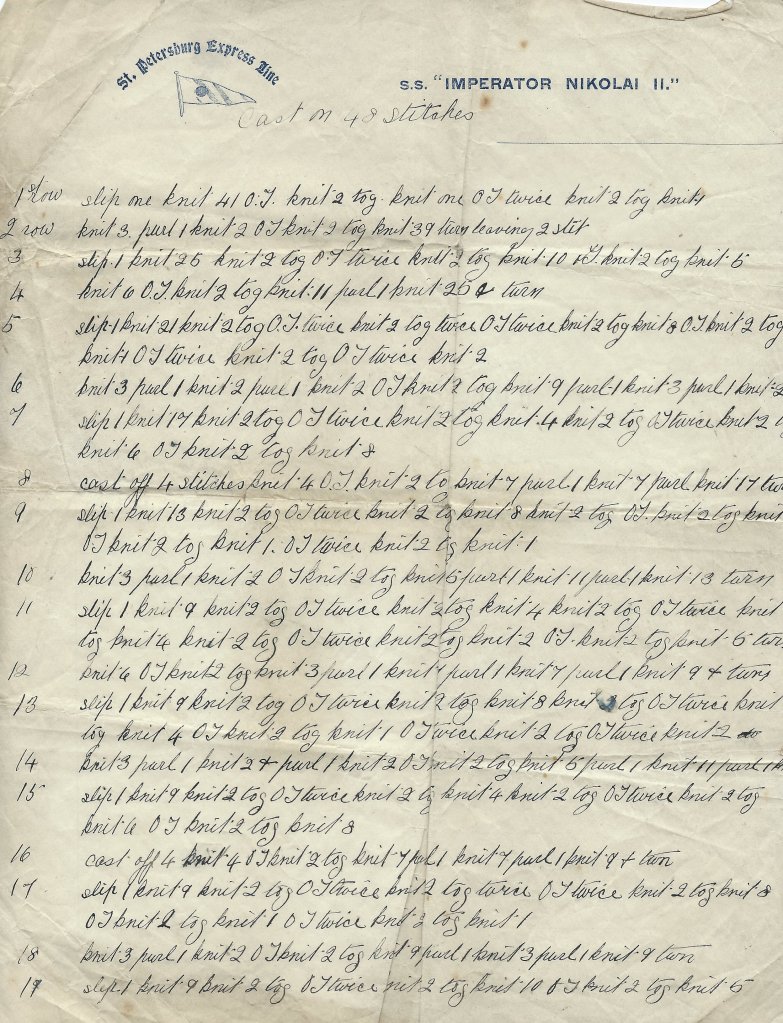

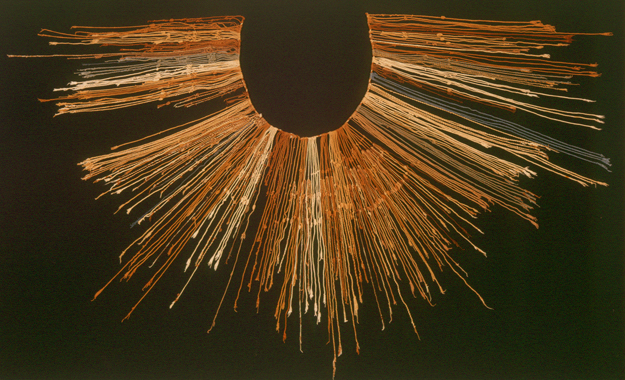

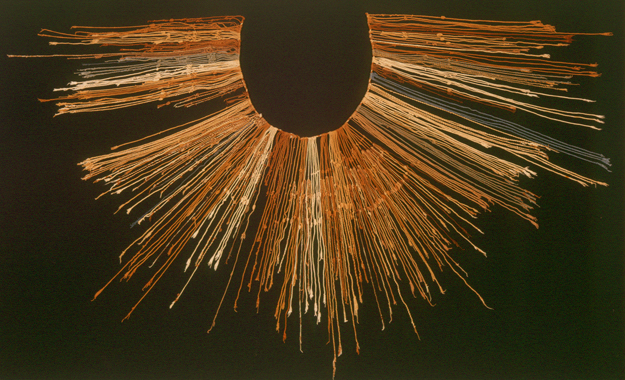

Memory tools and mnemonics vary from society to society. As Laura Miller argues a society that values the art of storytelling may approach the preservation of memories differently to a society that values the written above an oral tradition.[21] The Inca of ancient Peru used knots, each knot holding a specific value, to record their empire, from daily transactions to long-term tributes.[22] This mnemonic was used instead of the Western development of writing. Similarly in the 19th Century the Luba tribe of central Africa created memory boards as mnemonics to Luba history. These boards would be ‘read’ by experts and idiosyncrasies in the patterns, colours, materials and general shape would aid the ‘reader’s’ memory, evoking different interpretations by different ‘readers’ or even by the same expert upon different ‘readings’.[23]

The Incan practice of Quipu was a system for record keeping using cords and knots to record data.

Much of archival and memory literature uses such terms as traces, touchstones, goads, totems, and aides to describe a record’s relation to memory. Wallen describes archives as containing “droplets of time – observations, registrations, notations, pieces of data that can reawaken a memory.”[24] Similarly Miller calls the ’bits and pieces’ found in archives ‘engrams’, as being the stored fragments of an episode.[25] In this mnemonic sense records are not tangible memories but tangible artefacts for reconnecting with memories. Lowenthal argues that records (he uses the example of a photograph) are aids to memory but also a verification tool that our recollections are faithful to the past.[26] Psychologist Ulric Neisser likens the reconstruction of the past to the paleontological reconstruction of dinosaur skeletons – “[o]ut of a few stored bones …we remember a dinosaur.”[27]

Miller uses the example of a legal contract to expand the concept of archival traces as mnemonic devices. Whilst a contract is a legal agreement to ensure compliance between two parties it is also an “antidote to false remembering” as evidence of a transaction. More than this, the contract also recalls the parties’ own episodic memories.[28] In a Proustien sense archival documents are the physical representations of transactions and memories – the ‘madeleine’.

Archives now seek to create these ‘madeleines’ for under-recorded communities or for communities that don’t associate with a written tradition. Community engagement has become a central focus for archival institutions. By creating ‘traces’ in a multitude of media – photographs, sound recordings, moving images, visual art, monuments – archives are allowing communities to control how they wish to transmit their heritage, their memories.[29] Susan Sontag argues that the totemic properties of media, in particular photographs, can be more likely to resonate with individuals than a verbal slogan.[30] The Western focus on writing as the primary means of information and memory transmission is egotistical and lacks diversity in its vision of inclusivity.

Sontag argues that all memory is unique: that, as it dies with each individual, it is unreproducible.[31] Memories are literally a biological phenomenon literally only existing in a living individual. By extension mnemonics require an individual to read or interpret them and it is here that there is a need to separate the roles of individual and collective memory. Miller likens this experience to the fallen tree metaphor – that, like the tree, a records ‘sound’ may only be heard when there is someone there to hear it.[32] From a Western perspective we have disassociated ourselves from our own personal memories, giving control of them to archival and records management institutions for ‘safe-keeping’. Modern individuals have developed a symbiotic relationship with archives – donating their information and memories for safe-keeping and easy retrieval in out of body/off-site storage, and in return they contribute to a collective narrative. Wallen argues that in this sense autobiography is in part constructed out of the archive, that there is a “haunting” suspicion that someone or something knows us better than we know ourselves.[33] Archives allow individuals to connect with elements of their own past that has either been forgotten or was never registered as a memory, in what Olick and Robins call “graveyards of knowledge.”[34]

Biologically speaking memory traces in the hippocampus are thought to critically depend on stress steroid activation in the amygdala.[35] What this means is that the strongest memories that individuals keep tend to be created from emotionally charged situations. These individual memories of significant circumstances reflect well in a collective memory setting but this also means that individuals fail to capture more trivial memories. Archives are capable of capturing the most minute transactions on both an individual and a collective scale, something which human memory struggles to cope with.

To archives an individual memory is essentially irrelevant but it’s role in collective memory and narratives is essential. The fabric of collective memories is woven in the recording of individual memory strands. Sontag expanded on her argument about individual identities by stating that collective memory is not about remembrance but about stipulation – stipulation “that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.”[36] Archives build on this by allowing individuals to integrate their various persona pasts into a single common past that all members of a community come to collectively remember.[37] In the 19th Century it became a popular idea that the body could retain traces of the memories of ancestors, that memory and heredity were essentially the same thing.[38] Freud built on this concept through ‘ancestral memories’, his belief that organic memory theories could be psychoanalytically used to understand human culture.[39] Freud believed that the human unconscious was a repository for all past experiences and that it was forgetting, rather than remembering, that took [work] in the form of repression.[40] Darwin argued against this Lamarckian methodology. Stepping away from the biological feasibility of being able to connect with an ancestral memory, archives offer a very similar experience – archival records and documents grant access to an ancestral era that as Freud would argue, society has ‘consciously’ forgotten about.

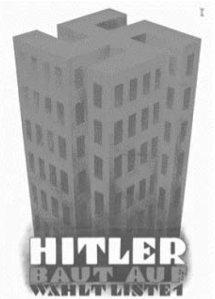

Collective memory has implications for Terry Cook’s observation of archival paradigm shifts. The current focus on identity and community has led to the use of archives for the construction of broad collective narratives and an over-reliance on ‘history’. Before this paradigm shift ‘the past’ would impact and direct collective memory not evidentially but mythologically. Now society uses collective memory, in the form of ‘history’ to shape the past. This presentist view argues that the past is moulded to suit present interest.[41] The Jungian perspective would argue that, because of this lack of mythology, society now looks to archives to create the necessary archetypes. In this sense memory is no longer a social practise. As Pierre Nora said, “There are lieux de memoire, sites of memory, because there are no longer milieux de memoire, real environments of memory.”[42] Society has lost its “memorial consciousness” because individuals have abandoned it.[43] King Thamus’ claim that those who adopt the practice of writing appear to have been accurate. Society adopted writing and as a result created institutions that could control their memories for them. This is what Derrida meant when he described the archive as hypnomnesic.[44]

In Charlie Brooker’s acclaimed TV series Black Mirror the episode entitled ‘Entire History of You’ exemplifies what dystopia might be created if individuals had constant access to their memories – making it impossible to forget, and possible to obsess. The unbearable weight of memory becomes overwhelming for individuals. There is too much injustice in the world, and too much remembering embitters humanity. As Sontag argues, “To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited.”[45]

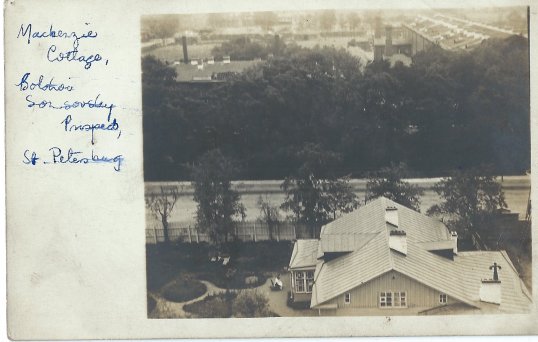

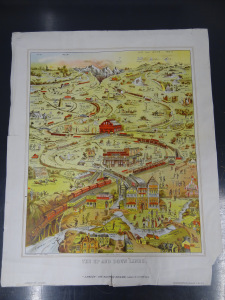

In many ways archives have supplanted memory. Archives claim to contain memory, but only the archival definition of memory. Artist Šehovic created an immersive piece to commemorate the Srebrenica massacre. In the aftermath of the event the archival record will show numbers of victims, personal information about them, and data relating to their lives.

‘Cups of Coffee’ by Aida Sehović’s is an installation consisting of coffee cups collected from Bosnian families around the world.

piece was designed to capture what eludes an archive – the lived experience. The project, called ‘Why are you not here?’, focused around the Bosnian tradition of sharing coffee. While archives will hold the data relating the victims’ lives they will never truly be able to capture the act of sharing coffee or, post-Srebrenica, not being able to share that coffee with a lost loved one. The archival record will be devoid of that emotional experience and will instead just capture a series of events and actors.[46] As Martine Hawkes argues, “[h]ow can a life reduced to a short line on a list – only admissible as a short line – be testified or borne witness to in its full weight and meaning?”[47]

It is not only in the area of capturing the un-capturable elements of memory that archives have struggled. As Olick and Robins argue, it is often difficult to reach a mnemonic consensus.[48] If we are to treat archives as the houses of mnemonic touchstones, society’s tangible collective memory, society should be ensuring that it truly is a collective memory. Sontag argues that there is no such thing as collective memory but instead there is ‘collective instruction.’[49] Archival interference extends much further than acquisition policies. Archivists now actively engage with records, leaving layers of procedural traces on them. Archives tend to reflect an elite and anti-populist world view. Firstly this means that the story represented is of national or international activity rather than local or regional experiences;[50] and secondly that various social groups – women, LGBT, ethnic minorities – can be sidelined, intentionally or otherwise, from the archival record. That is not to say that a mythologised collective memory would resolve the problem of elitism of social groups. Archival collections, according to Hillary Jenkinson, should be delivered to the archives whole and the archivist is not to meddle or adulterate the collections – but Jenkinson worked in an era before mass information production. In the 1950s Schellenberg revised Jenkinson’s premise and introduce appraisal in a move to control the sheer quantity of information being handled by archives. Eric Ketelaar invented the term archivalization [sic] meaning “the conscious or unconscious choice (determined by social and cultural factors) to consider something worth archiving.”[51] This element of the appraisal process identified records and memories and prioritised those which are deemed ‘worthy’. As a result of this archives were no longer holding ‘complete’ collections and as a consequence their ability to accurately reflect their societies was undermined.

Furthermore the practises of description and arrangement alter user interpretation of archival records. Archivists layer their own interpretations on a document or a series of documents, guiding a user to a certain conclusion. The archive represents the end of a certain kind of creative innocence, inferring self-consciousness and self-reflexivity onto records.[52] Archival interference has destroyed any notion that archives are capable of entirely recording the past.[53] With this in mind it is deceptive for archives to claim to hold memory, or even a complete set of untouched touchstones for accessing said memory – archivists are not clairvoyants, they cannot predict what records will trigger what memories in the future.[54]

The archival struggle with memory stems in part from the fact that archives simply don’t trust memory. Fixity is fundamental to archival records, cementing information in a stable and unchangeable format for transmission. Luciana Duranti examined the elements that underpin what makes a record factual, arguing that “[a] record is considered reliable when it can be treated as a fact in itself, that is, as the entity of which it is evidence.”[55] In addition to this Duranti proposed another element – authenticity – which requires that the record has not been manipulated or falsified after its creation and is therefore what it (the record) claims to be.[56] Matthew Innes argues that “oral tradition[s] can be very radically reshaped by changes in social, political and cultural contexts, and can fall into oblivion without acts of conscious destruction.”[57] Furthermore authentic records can trigger inauthentic memories. When Bruno Dössekker published his memoirs as a camp survivor of the Holocaust few had reason to doubt his account. Yet during the 1990s it was debunked as having been entirely fabricated. Dössekker had constructed an identity, Binjamin Wilkomirski, by absorbing accounts of camp life, the stories of extreme violence, the testimonies and histories and photographs, and they finally became him.[58] Dössekker’s exposure to Holocaust media had consumed him, having been so deeply affected by the event that he became an inadvertent victim. It is this element of uncertainty about the evidential quality of oral testimony and oral history that sits uncomfortably with archives. To paraphrase Franklin Roosevelt, records cannot be killed by fire, people die, but records never die, records are weapons[59] – whilst human memory can be eradicated, the physical counterparts to memory will remain. As previously mentioned, there is now a conscious effort to work through this problem and develop archival oral history projects to capture a greater selection of formats for collections. Perhaps archives will overcome this fear of fluidity in records, after all, as Greene puts it – “History is interpretation, and as such it is subject to exactly those same societal biasses that are supposedly the weakness of “memory”.”[60]

Whether archives have undermined memory is very much a Platonian vs. Aristotilian debate. King Thamus argued that society would become forgetful as a consequence of the invention of writing, an idea that Nora believes has become reality in the modern world. Conversely Aristotle believed that individuals, born like blank slates, would amass memories and be bettered for this amassing. Should, or even could, a society capable of creating such large amounts of ‘memory’ entrust its preservation to human minds? Conversely, should this responsibility be given to archives? Derrida vehemently sides with King Thamus, arguing that archives “incite forgetfulness, amnesia, the annihilation of memory, as mnēmē or anamnēsis” and that the rigid formula of the archive eradicates what cannot be archived.[61] Conversely Sontag argues that too much value has been assigned to memory but not enough to thinking.[62] Perhaps the act of writing and recording has freed the human mind from its bonds of memory to fulfil a greater potential of ‘knowledge’.

There is an elitist element of archival thought which values the tangible over the intangible and so, fundamentally, archives have undermined memory – intangible memory created by a human no longer has the value that it once had. Society should question the archival monopoly on memory and ask why a document of an event is apparently more representative than a human that actually experienced it? But society does not consciously remember and as a consequence society is subconsciously forgetting much of its cultural and collective memory. Archives have depersonalised memory and made it own-able, the classic oral traditions eroded by modernity.

Archives have however created and preserved tangible mnemonic devices in order to help recall the intangible memories of the past. Like Cicero’s ‘treasure-house of all things’ and St. Augustine’s ‘inner chamber, vast and unbounded’, archives have become society’s memory repositories,[63] not society’s memory. Miller argues that archives and archivists risk professional marginalisation if they continue to use the outdated metaphors of ‘archives as memory’ instead of archives as mnemonics.[64] Derrida described the conflict between writing and speech as a ‘pharmakon’[65] – that which whilst healing, also poisons. Archives have undermined the human ability to ‘remember’, but at the same time have found a way to reconnect society to their forgotten memories. The archival relationship with memory needs to be symbiotic – obliged to collect humanity’s memories in whatever format they may be and, in return, society can outsource their memory functions. Archives house society’s mnemonics so that society can not necessarily remember but recollect.

Ginny Dawe-Woodings, BA

- Plato, Phaedrus, (Edited by Harvey Yunis, 2011)

- Terry Cook, ‘Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting archival paradigms’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2013), Vol. 13, p. 101

- Steven Roger Fischer, History of Writing, (2001), p. 11

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 106

- Terry Cook, ‘Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting archival paradigms’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2013), Vol. 13, p. 96

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 111

- Anthea Josias, ‘Toward an understanding of archives as a feature of collective memory’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2011), Vol. 11, p. 109

- Terry Cook, ‘Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting archival paradigms’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2013), Vol. 13, p. 104

- Ibid, p. 102-103

- Jeffrey K. Olick, Joyce Robbins, ‘Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practises’ in Annual Review of Sociology, (Annual Reviews, 1998), Vol. 24, p. 122

- Steven Rose, The Making of Memory, (Anchor Books, 1992), p. 60

- Jeffrey Wallen, ‘Narrative tensions: The Archive and the Eyewitness’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, (2009), Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 269

- Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects, (2012), Chapter 13

- Rachel Hardiman, ‘En mal d’archive: Postmodernist Theory and Recordkeeping’ in Journal of the Society of Archivists, (2009), Vol. 30, No. 1, p. 32

- Society of American Archivists, Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology – ‘Total Archives’, (http://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/t/total-archives, accessed 29th March 2015)

- Jeffrey Wallen, ‘Narrative tensions: The Archive and the Eyewitness’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, (2009), Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 261

- Terry Cook, Joan M. Schwartz, ‘Archives, Records, and Power: From (Postmodern) Theory to (Archival) Performance’ in Archival Science, (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), Vol. 2, p. 179

- Sue McKemmish, “Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: A Continuum of Responsibility” in Proceedings of the Records Management Association of Australia 14th National Convention, RMAA, Perth, Australia, (1997) referenced in Brien Brothman, ‘The Past that Archives Keep: Memory, History, and the Preservation of Archival Records’ in Archivaria, (2001), Vol. 51, p. 56

- Mark A. Greene, ‘The Messy Business of Remembering: History, Memory, and Archives’ in Archival Issues, (2003-2004), Vol. 28, No. 2, p. 97

- Anthea Josias, ‘Toward an understanding of archives as a feature of collective memory’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2011), Vol. 11, p. 100

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 121

- Steven Roger Fischer, History of Writing, (2001), p. 14

- Ibid, p. 22

- Jeffrey Wallen, ‘Narrative tensions: The Archive and the Eyewitness’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, (2009), Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 261

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 111

- David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country, (1985), p. 257

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 111

- Ibid, p. 115-116

- Anthea Josias, ‘Toward an understanding of archives as a feature of collective memory’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2011), Vol. 11, p. 97-98

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (Penguin Group, 2003), p. 76

- Ibid, p. 76-77

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 116 Jeffrey Wallen, ‘Narrative tensions: The Archive and the Eyewitness’ in Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, (2009), Vol. 7, No. 2, p. 269-270

- Jeffrey K. Olick, Joyce Robbins, ‘Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practises’ in Annual Review of Sociology, (Annual Reviews, 1998), Vol. 24, p. 111

- Adam K. Anderson, Yuki Yamaguchi, Wojtek Grabski, Dominika Lacka, ‘Emotional memories are not all created equal: Evidence for selective memory enhancement’ in Learning & Memory, (2006), Vol. 13, p. 715

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (Penguin Group, 2003), p. 76-77

- Anthea Josias, ‘Toward an understanding of archives as a feature of collective memory’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2011), Vol. 11, p. 99

- Daniel Punday, ‘Foucault’s Body Tropes’ in New Literary History, (2000), Vol. 31, No. 3, p. 518-519

- Ibid, p. 519

- Jeffrey K. Olick, Joyce Robbins, ‘Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practises’ in Annual Review of Sociology, (Annual Reviews, 1998), Vol. 24, p. 109

- Anthea Josias, ‘Toward an understanding of archives as a feature of collective memory’ in Archival Science, (Springer, 2011), Vol. 11, p. 96

- Pierre Nora, ‘Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire’ in Representations, (University of California Press, 1989), Vol. 26, p. 7

- Ibid, p. 12

- Jaques Derrida, Archive Fever, (The John Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 11

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (Penguin Group, 2003), p. 103

- Martine Hawkes, ‘Containing testimony: archiving loss after genocide’ in Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, (Routledge, 2012), Vol. 26, No. 6, p. 937

- Ibid, p. 939

- Jeffrey K. Olick, Joyce Robbins, ‘Social Memory Studies: From “Collective Memory” to the Historical Sociology of Mnemonic Practises’ in Annual Review of Sociology, (Annual Reviews, 1998), Vol. 24, p. 127

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (Penguin Group, 2003), p. 76

- Terry Cook, ‘Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting paradigms’ in Archival Science, (2013), Vol. 13, p. 106

- Eric Ketelaar, ‘Tacit Narratives: The Meanings of Archives’ in Archival Science, (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001), Vol. 1, p. 132-133

- Stuart Hall, ‘Constituting an archive’ in Third Text, (2001), Vol. 15, No. 54, p. 89

- Terry Eastwood, ‘What is Archival Theory and Why is it Important?’ in Archivaria, (1994), Vol. 37, p. 130

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 122-123

- Luciana Duranti, ‘Reliability and Authenticity: The Concepts and Their Implications’ in Archivaria (1995), Vol. 39, p. 6

- Ibid, p. 7-8

- Matthew Innes, ‘Memory, Orality and Literacy in Early Medieval Society’ in Past & Present, (1998), Vol. 158, p. 34

- Amy Hungerford, “Memorizing Memory’ in The Yale Journal of Criticism, (The John Hopkins University Press, 2001), Vol. 14, No. 1, p. 88

- ‘Books are weapons in the war of ideas’, Library of Congress Prints and photographs Division, Washington D.C., Reproduction number: LC-USZC4-4267

- Mark A. Greene, ‘The Messy Business of Remembering: History, Memory, and Archives’ in Archival Issues, (2003-2004), Vol. 28, No. 2, p. 97

- Jaques Derrida, Archive Fever, (The John Hopkins University Press, 1995), p. 11

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (Penguin Group, 2003), p. 103

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 107

- Laura Miller, ‘Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives’ in Archivaria, (2006), Vol. 61, p. 108-109

- Jaques Derrida, Plato’s Pharmacy in Dissemination, (1981)

50.081707

-5.161460