It is not easy to define what it takes to make a ‘distinctly fascist’ artistic style when it is difficult enough to identify what makes fascism itself ‘distinctly fascist’. Stanley G Payne defines fascism as embodying certain, not exclusive, typographical descriptions: anti-liberalism; anti-communism; the creation of a new nationalist authoritarian state; goals of empire or of revolution; the creation of an idealist, voluntarist creed, normally involving the realisation of a new form of modern, self-determined secular culture; emphasis on a romantic and/or mystical aesthetic; extreme stress on masculinity and patriarchy; and national unity.[1]

George L. Mosse argues for fascism as a ‘civil religion’, a non-traditional faith which uses liturgy and symbols to make its belief come alive,[2] and that fascist aesthetics need to be put into this framework. Ulrich Schmid’s explanation is that fascism can be understood as a total work of art where each element fits stylistically and so not only the artistic aesthetic but also styles of behaviour, clothing and even speech are basic manifestations of the fascist reality.[3]

Each pre-Second World War fascist regime sought to create its own particular over-arching aesthetic, incorporating many of the above characteristics, to help shape public attitudes. The Nazi version was all-encompassing: militaristic symbolism and dress; architectural style and embellishment; and all aspects of art: theatre, film, sculpture and painting.

Schmid argues that there is a widespread cliché identifying fascist aesthetics with monumental neo-classicism,[4] and Nazi Germany did largely come to fit this stereotype. However, as demonstrated in Italian and Spanish fascist aesthetic movements, fascism could also experiment with Modernist ideas such as futurism and cubism that had become anathematised in Germany. The early 20th century had seen Modern art flourish in the USA and Europe, including Germany. However following Germany’s defeat in the First World War and the shame and humiliation associated with its surrender, many Germans, and not only those who supported the NSDAP, turned against anything seen as liberal or foreign.[5] The German population began to look inwards, favouring art that celebrated parochial and provincial life: a new aspiration but ultimately a return to their roots.

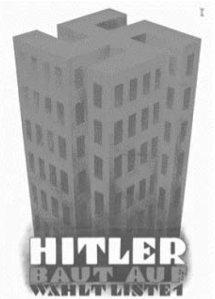

Even in the conservative artistic climate of the time, very early Nazi art briefly brushed with elements of modernism: Willy Engelhardt’s 1933 election poster (Figure 1) used a Bauhaus-style building to create a visual metaphor for Hitler’s ‘modern position,[6] while in the same year Goebbels unsuccessfully attempted to integrate what he called ‘Nordic Expressionism’ into the official Nazi art movement. He failed because he was unable to overcome Hitler’s own preference for monumental classicism,[7] the style that would ultimately define Nazi art.

(Figure 1) Willy Engelhardt – Poster for German Elections, ‘Hitler Builds Up’ (1933)

After coming to power in early 1933, the Nazis used the threat of Modernism to ignite the debate over the National Socialist kulturpolitik and how to manage cultural policy.[8] Kurt Karl Eberlein commented: “This [modern] art is still ‘culture’, hence uncomfortable, alien to the people. The fault lies neither with the state nor with the individual, but with that art which is cut off from blood and soil”.[9] Modern art became associated with chaos and foreign liberalism; a style to be despised; and was labelled with some of Nazism’s favourite pejorative adjectives: ‘degenerate’, ‘Bolshevik’ and ‘Jewish’.[10]

Within the favoured style of classicism, Nazi art emphasised several key themes and subjects which broadly accorded with Payne’s typography. The idea of ‘Blut und Boden’ (Blood and Soil), first propounded by 19th Century agrarian romanticists, and given greater impetus after the First World War by the likes of Shultz-Naumburg and Darré,[11] was a romantic idea both of an idealised re-adoption of rural values and, perhaps more importantly, of a mystical link between the German people and their homeland: of national unity. The romanticism was often emphasised by the use of mythological imagery, almost exclusively Greek and Nordic. The non-mythologised human form was also explored, not only the literal physiology but also as a metaphorical embodiment of health and strength. Militarism and male dominance were prominent themes, as was family life, often depicting strictly defined gender roles.

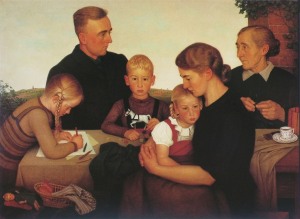

This division of gender roles is exemplified in Adolf Wissel’s ‘Farm Family from Kahlenberg’ (1939) (Figure 2), a portrait of a seemingly idyllic Aryan family. The father appears behind the rest of the family casting a somewhat detached but domineering eye over his brood, a grandmother knits, children play and, at the centre, the mother comforts the youngest child. A clear vision of a patriarchy with women subordinated by the prevalent ‘kinder, küche, kirche’ ideology. Adam explains that “If man was shown as the dominator of nature, woman was represented as nature itself”.[12]

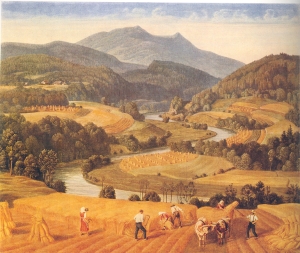

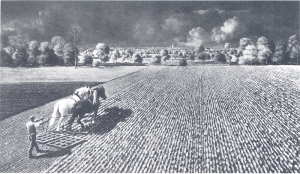

Payne identifies romanticism and mythology/mysticism as elements that help develop an idealised creed or culture. Karl Alexander Flügel’s ‘Harvest’ (1938) (Figure 3) depicts the idyllic life of country folk working in a perfect landscape and evokes not only a bountiful land but a hardworking population; echoing the ‘blood and soil’ agrarian ideal. It reflects the same allegorical arcadia seen in Caspar David Friedrich’s works from a century earlier and is representative of a return, in both content and style, to the original neo-classicist landscape painters. Werner Peiner’s ‘German Soil’ (1938) (Figure 4) and Julius Paul Junghanns’ ‘Hard Work’ (1939) (Figure 5) also have a similar romantic focus on the German countryside and the people living there. Even the titles of the pieces hammer home the Nazi ethos.

(Figure 3) Karl Alexander Flugel – ‘Harvest’, (1938)

(Figure 4) Werner Peiner – ‘German Soil’, (1938)

(Figure 5) Julius Paul Junghanns – ‘Hard Work’, (1939)

In ‘Rewards of Work’ by Gisbert Palmié (1933) (Figure 6) the idealised real world of ‘Harvest’ is extended to introduce elements from mythology. The central Aryan female character bears a superficial similarity to Botticelli’s Venus but she is now surrounded by an idealised agrarian idyll. While echoing classical style, the emphasis has moved from the celebration of a mythological or entitled elite to celebrating rural and pastoral artisans.

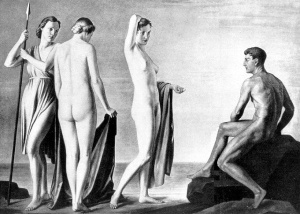

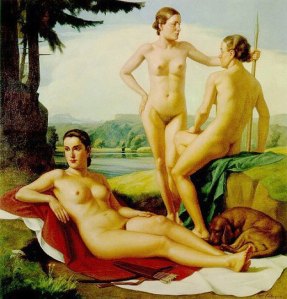

Alfred Rosenberg himself highlighted the importance of Greek mythology to the Nazi aesthetic, saying that “The Nordic artist was always inspired by an ideal of beauty. This is nowhere more evident than in Hellas’s powerful, natural ideal of beauty”.[13] Adolf Ziegler’s works the ‘The Four Elements’ (1937) (Figure 7) and ‘Judgement of Paris’ (1939) (Figure 8) extend the use of mythology still further, being full depictions of ancient Greek myths in a romantic classical style.

The communication of values and messages by allegory and metaphor was important but high value was also placed on representations of fitness and wellbeing, as characterising racial purity and superiority, the Aryan ideal. The identification of the naked man with the ideal of classical beauty and heroism was a ubiquitous sentiment in National Socialist art and popular culture. Hubert Wilm stated: “Representation of the perfect beauty of a race steeled in battle and sport, inspired not by antiquity or classicism but by the pulsing life of our present-day events”.[14]

Artists were encouraged by the Reich Chamber for the Visual Arts to attend courses in gymnasiums and sport complexes to improve their life drawing. This helped develop a specific style of drawing, far removed from drawings of ‘real life’, which concentrated on nude studies of virile and sturdy models in strong or sporting poses: every element of the human form needed to impart strength, discipline and force.[15] ‘Sports of the Hellenics’ and ‘Olympia and the German Spirit’ were popular exhibitions aimed at promoting the bond between athleticism and art. The 1936 Berlin Olympics was an opportunity not only to showcase Germany’s sporting prowess and superiority but also to create art. Leni Riefenstahl’s film ‘Olympia – Feast of Nations’ (1938) fades between shots of ancient sculptures and sports men and women, binding contemporary life with classic forms and traditions.

Amongst the best examples of the human form in Nazi arts were the sculptures of Arno Breker whose works echoed the works of classical Greece and Rome. Paintings such as Ivo Saliger’s ‘Diana’s Rest’ (1940) (Figure 9) depict the human form as athletic and wholesome. Many paintings are romanticised in their visualisations of humanity: Leopold Schmutzler’s ‘Farm Girls Returning from the Fields’ (1937) (Figure 10) and Oskar Martin-Amorbach’s ‘The Sower’ (1937) (Figure 11) show hard-working, healthy and active characters embracing their everyday tasks.

(Figure 9) Ivo Saliger – ‘Dianas Rest’, (1940)

(Figure 10) Leopold Schmutzler – ‘Farm Girls Returning From the Fields’, (1937)

(Figure 11) Oskar Martin-Amorbach – ‘The Sower’, (1937)

The German population became idolised in statuary and on canvas. As with much fascist art the images did not necessarily represent reality but an idealised, even exaggerated version of it. All authoritarian regimes wish to inspire and reinforce feelings in their populations: in this case the message was that, under the NSDAP, the German people were healthy and strong: past, present and future. The naked human form held no fear for the Nazis, provided it was attractive, healthy, and Aryan.

This concept of a fit, healthy people sat well with the idea of eugenics promoted by the Nazis. Ziegler’s ‘Judgement of Paris’ (1939) (Figure 8), while a representation of an episode from Greek mythology, can also be interpreted as a narrative for this eugenics sentiment. The mythical tale of Paris picking the most beautiful from three goddesses: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, reflects the high value placed on Aryanism and human aesthetics in real life as well as in art. Judgement of the goddesses based on their beauty is a visualisation of the selection of partners in Germany. Again, art is being used to subtly influence German culture and thinking.

Health and strength, along with masculinity and patriarchy, were also glorified through militarism in art. Women were subordinate; men in comparison were expected to support and defend their country. The ‘warrior’ became a key figure, embodying persistence, victory and a fierce jingoism. Militarism also gave a visual representation of the Nazi philosophy that there existed a perpetual ‘struggle’ between races which could only be solved by armed conflict: the superior race being the victor.

Conrad Hommel’s ‘The Leader and Commander in Chief of the Army’ (1940) (Figure 12) highlights this respect for the ‘warrior’. The full length portrait of a uniformed Hitler standing in a powerful pose does not endear the subject to a viewer, it is intended to emphasise strength and develop emotions of respect, admiration and gratefulness: this is a leader fighting for Germany and her ideals in difficult times. Emil Scheibe’s painting ‘Hitler at the Front’ (1942) (Figure 13) similarly shows Hitler as a military leader; supporting his soldiers; willing them to victory.

(Figure 12) Conrad Hommel – ‘The Leader and Commander In Chief Of The Army’, (1940)

(Figure 13) Emil Scheibe – ‘Hitler at the Front’, (1943)

Mosse’s ‘civic religion’ concept also informs Nazi aesthetics and artwork. Whilst paintings tended to be devoid of overt references to traditional religions (other than anti-Semitic messages), they often used similar styles and methods to historical religious artworks. Symbolism and iconography were popular, as well as the use of triptychs and friezes. The repeated use of the hakenkreuz, eagle and totenkopf in paintings, as well as throughout wider society, echoed the cross or the nimbus of traditional religious symbolism. All of this helped create a quasi-religious aesthetic.

Arthur Kampf’s ‘Der 30 Januar 1933’ (1939) (Figure 14), commemorating the Nazi seizure of power, emphasises Swastika emblazoned flags and the Nazi salute alongside the triumphant scenes of marching SA Brownshirts beneath the Brandenburg Gate. This conveys and reinforces so many fascist messages.

(Figure 14) Arthur Kampf – ‘Nazi Seizure of Power’, (1938)

(Figure 15) Hans Schmitz-Wiedenbruck – ‘Workers, Soldiers, Farmer’, (1940)

Hans Schmitz-Wieden’s triptych ‘Workers, Soldiers, Farmer’ (1940) (Figure 15) also brings together several of the key artistic motifs and messages of the Third Reich. The larger centre panel shows representatives of the three branches of the military whilst, either side, are miners and a farmer at work. The triptych format echoes religious works, as does the iconography of the Swastika, but the clear message is that, while all activities are important, they are there to support the most important: those fighting for the Reich.

The creation and veneration of martyrs to the cause also existed in the Nazi ‘religion’: the ultimate example being Horst Wessel, an SA Sturmführer killed in 1930. Most famously commemorated by the “Horst Wessel-Lied” which became the NSDAP anthem, effectively Germany’s joint national anthem, his image became ubiquitous in photographs, posters and more physical memorials.

Developing a fascist aesthetic to support a political philosophy demands that it is widely disseminated. The Nazis created museums and galleries; various art magazines such as ‘Die Kunst im Deutschen Reich’ were published; miniaturisations of famous paintings appeared on stamps, cigarette cards and postcards; films such as Riefenstahl’s were praised internationally; statues placed in parks and town squares; the swastika was everywhere. 1937 saw the first ‘Great German Art Exhibition’, where works by painters and sculptors such as Wissel and Breker were displayed alongside those of original neo-classical painters like Casper David Friedrich, defining a continuum of what was distinctly ‘German art’. These exhibitions drew vast crowds which would praise the art not just stylistically but also for its content.

Having created the means of disseminating their favoured aesthetic, the Nazi regime accentuated that aesthetic by denigrating and banning that which did not fit: artworks they called ‘Entartete Kunst’ (degenerate art) which included work by communists, Jews, foreign artists and other undesirables. Otto Dix, Marc Chagall and Max Ernst were all excluded: even Max Liebermann, the president of the Prussian Academy of Arts, was denounced by the far right in the 1930s. This was not entirely down to the content of his art, which focused mainly on the peasantry and the working class, but because of his “indebtedness to foreign models, his internationalism, [and] his rejection of ideology in art”.[16] The ‘Degenerate Art Exhibition’ was mounted in 1937 to contrast with and identify a clear divide between the acceptable fascist, German art of the ‘Great German Art Exhibition’ and unacceptable ‘degenerate’ art.

Compared to the fascist art of Italy and the Socialist art of Stalinist Russia, Nazi Germany’s art demonstrated its own rather conservative, traditionalist individuality. Italian fascist art embraced elements of modernism such as futurism and took a progressive approach. Soviet art also toyed with Modern styles such as cubism and impressionism and, while it favoured Socialist and Heroic realism as generic styles, it was less restrictive and critical of other artistic movements. Nazi art on the other hand had regressed to a neo-classical style popular a century earlier whilst at the same time excluding, even banning, other artistic styles. Katya Mandoki argues that the art of the NSDAP was unique because of six substitutions: “the substitution of religion by the instrumentalisation of art; the substitution of art by propaganda; the substitution of propaganda by indoctrination; the substitution of culture by monumentalism; the substitution of politics by aesthetics; and the substitution of the aesthetic by terror”.[17]

Within its unique conservative style Nazi art was purposeful, with content chosen less for aesthetic appeal and more for usefulness in the ‘bigger political picture’. It achieved much in terms of embodying and communicating the wider fascist ethos of the NSDAP: reinforcing its back-story of a pure race and a country with both a mystical past and a great future, a ‘thousand-year Reich’, that would be delivered if the people believed in the ‘quasi-religious’ values of Nazism – military and moral strength together with an intolerance of weakness, liberal values and, above all, the evils and degeneracy of communism and Judaism. It is interesting that the art created was so distinct and clear in its message, such a quintessential fascist aesthetic, that almost seventy years later the material is still something of a taboo with many authors putting disclaimers in their work when discussing Nazi art, seeking to avoid condoning the content.

- Stanley G. Payne, ‘Fascism as a ‘Generic’ Concept’ in Aristotle A. Kallis, The Fascism Reader (2003), p. 84-85

- George L. Mosse, ‘Fascist Aesthetics and Society: Some Considerations’ in Journal of Contemporary History (1996), Vol. 31, No. 2, p. 245-246

- Ulrich Schmid, ‘Style versus Ideology: Towards a Conceptualisation of Fascist Aesthetics’ in Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions (June, 2005), Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 128

- Ibid, p. 129

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (1996), p. 19

- Kurt Karl Eberlein, Was ist deutsch in der deutschen Kunst? (Verlag E. A. Seemann,1933) referenced in George L. Mosse, Nazi Culture (1966), p. 165

- Peter Adam, The Art of the Third Reich (1992), p. 35

- Ibid, p. 29

- Ibid, p. 150

- Ibid, p. 24

- Ibid, p. 64

- Ibid, p. 179

- Peter Paret, German Encounters With Modernism 1840-1945 (2001), p. 200

- Katya Mandoki, ‘Terror and Aesthetics: Nazi strategies for mass organisation’ in Renaissance and Modern Studies (1999), Vol. 42, No. 1, p. 65